Christophoros Katsadiotis, thank you for graciously sharing your world and artistic journey with the readers of this interview.

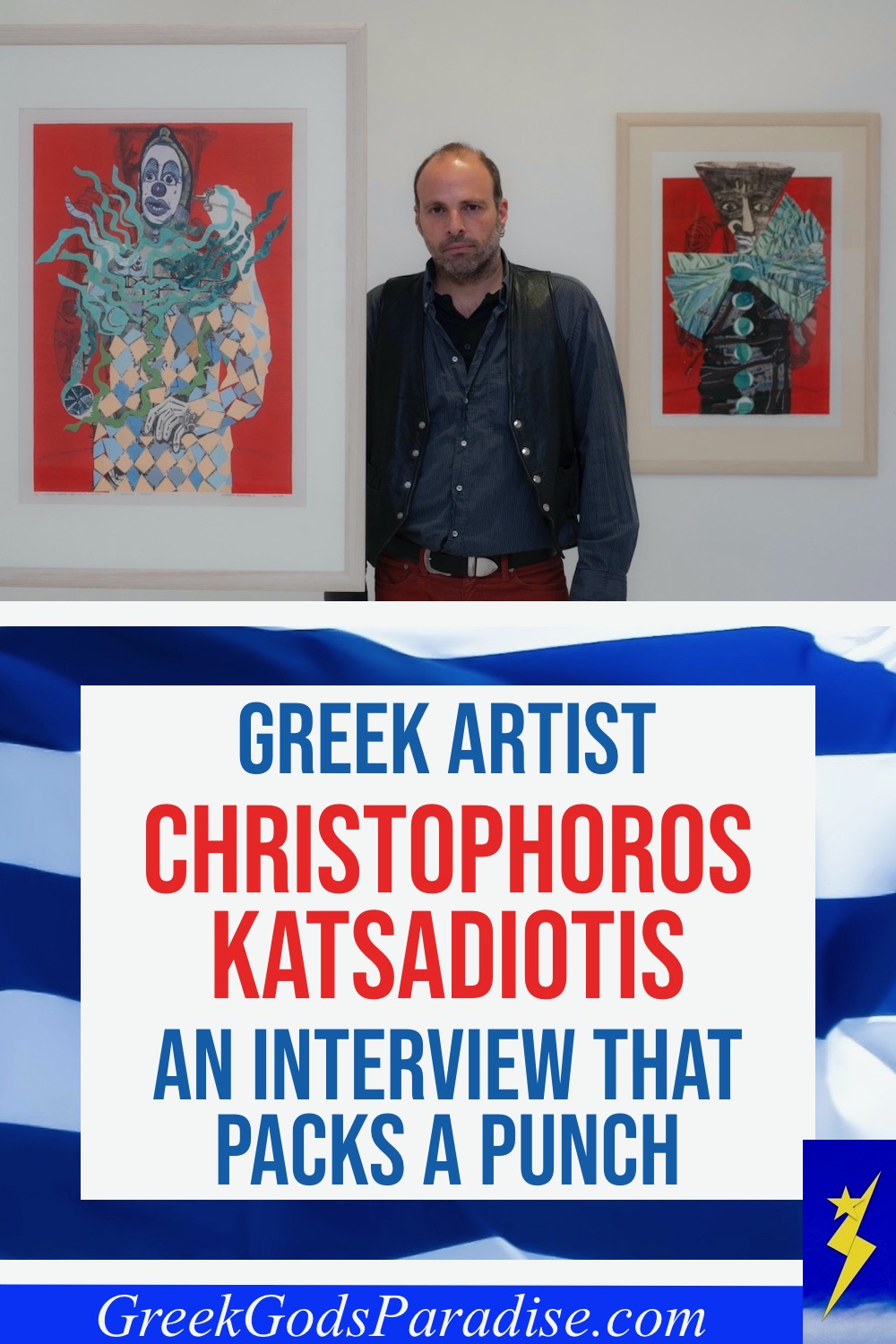

You first caught my attention during a shocking incident at the National Gallery in Athens in March 2025. An enraged Greek MP stormed into the gallery and vandalized your works, claiming the destruction was justified because he considered them blasphemous. Let’s begin this interview by exploring that powerful event.

Interview with Christophoros Katsadiotis: Exploring Art and Life

Could you share your experience of exhibiting at the National Gallery in Athens? How did you feel when you discovered that your works had been destroyed?

I felt the violence—not so much against my artwork, but as an act of desecration against democracy and the political system itself. It was a clear act of censorship, targeting freedom of expression, and more specifically, censorship of art. Artistic freedom is constitutionally protected.

These were art pieces in a public exhibition space. No one was forced to attend the show… And if someone felt offended, they could’ve taken legal action. I find it inconceivable that if something bothers us, we go in and destroy it. That mindset doesn’t belong in a democracy—it belongs with the Taliban.

It means that the two individuals who committed this act, and the party backing them, are barbaric, uneducated, and uncultured. You know, this exhibition was presented in dialogue with Goya’s engravings from 1789—prints that, back then, were pulled from circulation by the church because they criticized human vices, church authority, and the upper class. And here we are, 226 years later, facing the exact same problem. No progress whatsoever…

Distortion in art is a form of visual expression—it’s been around since the 1500s in Catalan painting, and by the 17th century, grotesque elements were appearing in iconography and murals…

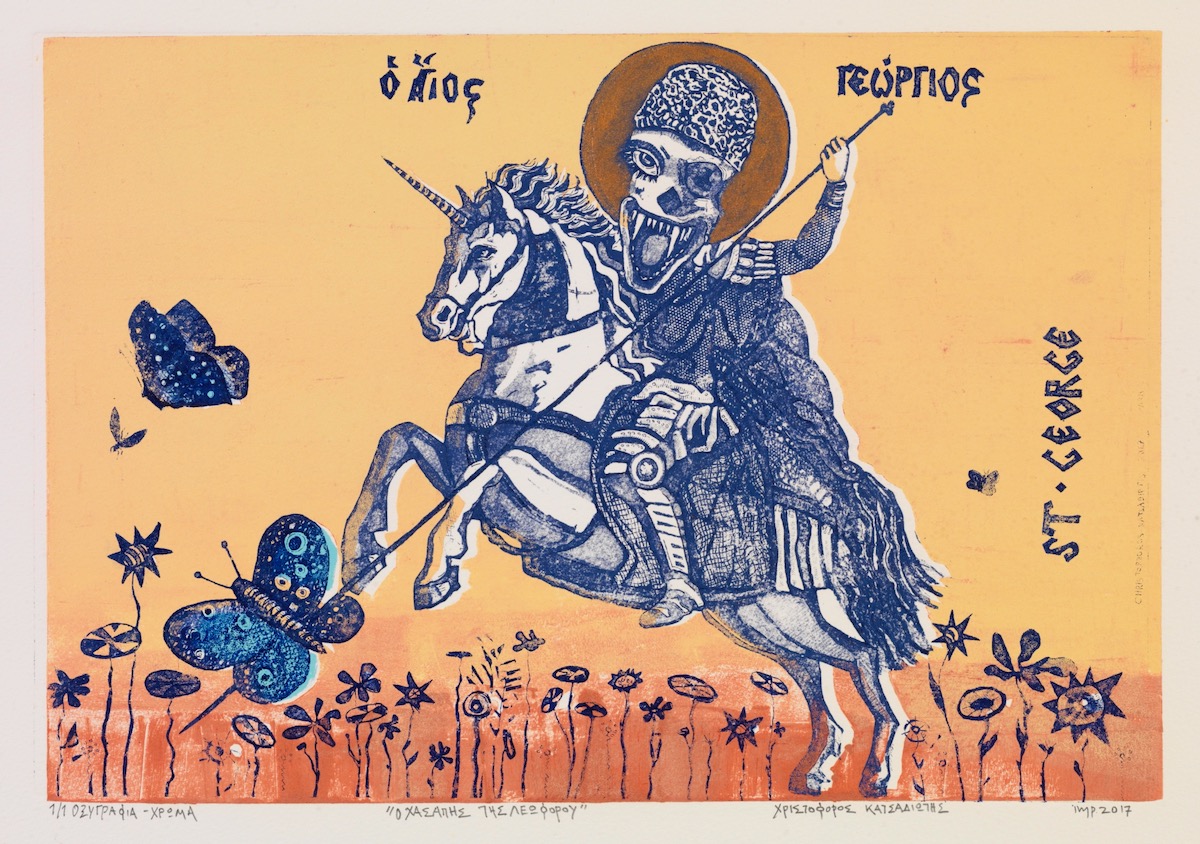

Could you show us a photo of one of the exhibited works that, in your opinion, the MP and religious authorities deemed blasphemous? The more controversial, the better! Was it your intention to provoke these narrow-minded individuals? What message were you aiming to convey with this particular piece?

The piece in question is titled “The Butcher of the Boulevard.” It shows Saint George having taken the form of a dragon, and the dragon has turned into a butterfly. The Metropolitan of Corfu accused me of being “perverse” because the butterfly symbolizes the soul. But he forgets that Saint George is the patron saint and symbol of the Greek army, the British Royal Army, and he was also the protector of the Crusaders—those who, in their time, waged wars “in the name of God,” from the 11th to the 15th centuries.

So how can Saint George—or any saint who was a warrior, ready to kill non-believers and drench their hands in blood—be seen as a messenger of God, love, peace, compassion, harmony, and respect?

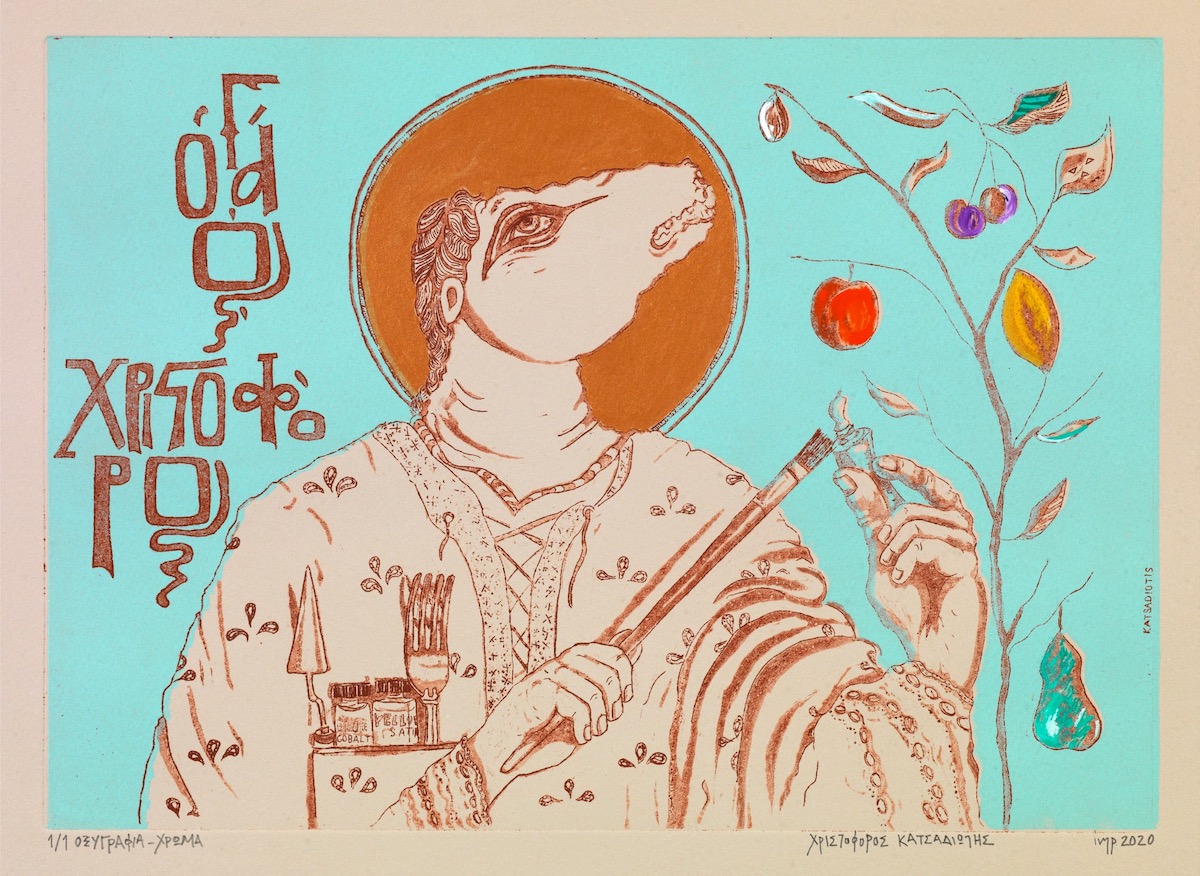

The same goes for my work “Saint Christopher”, which they criticized because he has the face of a dog, a fork in his pocket, a paintbrush in one hand, and a tube of paint in the other.

Few people know that in Balkan countries and across Eastern Europe, even in Russia, Saint Christopher is the only saint depicted with an animal head—specifically a dog—because they say he was extremely ugly, bloodthirsty, and came from a cannibalistic village during the Middle Ages. The church now claims that this was his appearance before being “civilized” by the Christian faith. With Christianity, he became human and purified… Today, he’s depicted with a human head.

It’s almost laughable—church figures destroyed ancient temples and now refuse to acknowledge that their theology borrowed heavily from ancient Greek mythology, with roots in paganism. They don’t even believe in Darwin!

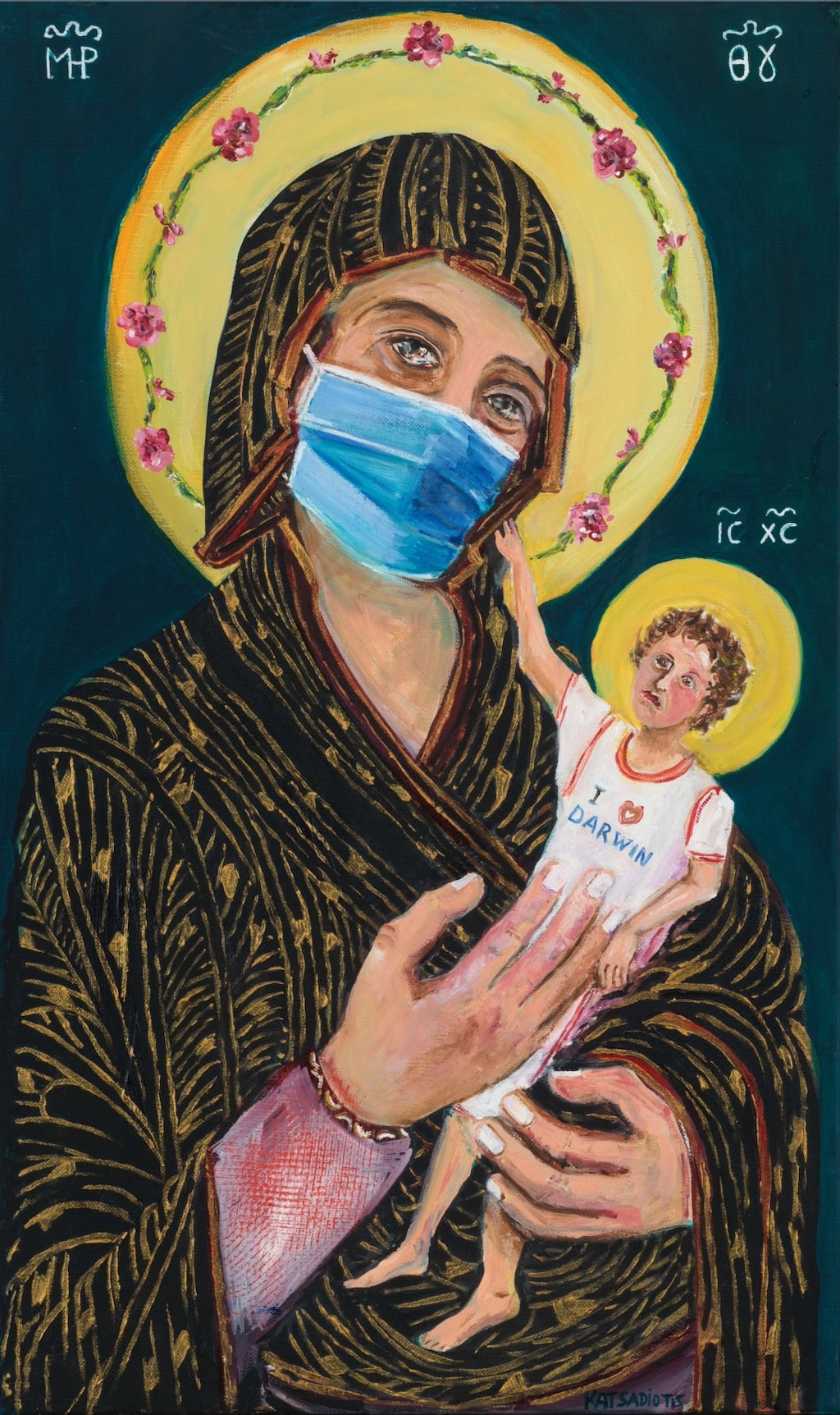

“I love Darwin”, Oil on canvas, 54.7X33 cm., 2021.

I’d love to hear about your spiritual beliefs, if you’re comfortable sharing. Do you identify with a particular faith, like Greek Orthodoxy, or lean more toward atheism or agnosticism? Maybe you draw inspiration from Buddhism, the ancient Greek gods, or follow a unique spiritual path. Whatever your view, I’m curious how it shapes your worldview and artistic voice.

I respect everyone’s religion. I don’t like insulting people or their beliefs. But as an artist, my job is to ask questions. To present my point of view. In Greek, the word for visual artist—εικαστικός—comes from the verb εικάζω, which means to “speculate” or “imagine.” I shape emotions.

My role as an artist isn’t about decorating living rooms and shop windows, painting flowers and sunsets to match your curtains. It’s to raise questions and engage with the pressing issues of our time… on a social level.

Personally, when I walk into a church and look at the icons, I feel threatened by the saints. It’s like they’re saying, “Join us, or you’re our enemy. You’re a sinner destined for eternal damnation.” I don’t like that mentality. The Gospel says God doesn’t need human defense. It strongly supports human freedom in all aspects. Christ only expresses anger in the Gospel toward wealth and hypocrisy—not even toward his enemies. He understands them and even prays for them. Neither politicians nor church figures follow those teachings…

As for what I believe in: I believe in the power of nature and in circumstances. I belong to no religion.

I honor the god Dionysus.

Most religions unfortunately divide societies instead of uniting people… They threaten, label people as good, bad, moral, immoral, sinful… They are a mechanism to maintain social order and enable painless political decisions – always for someones economic gain. It is all strategic. Just think how many wars are fought “in the name of God…”.

I use religious figures to express my concern that the future of humanity is uncertain due to our actions. I fear that our future is our own self-destruction. How could the face of Virgin Mary be painted without an expression full of concerns and worries…? Take a look around us, all the wars and inequalities…

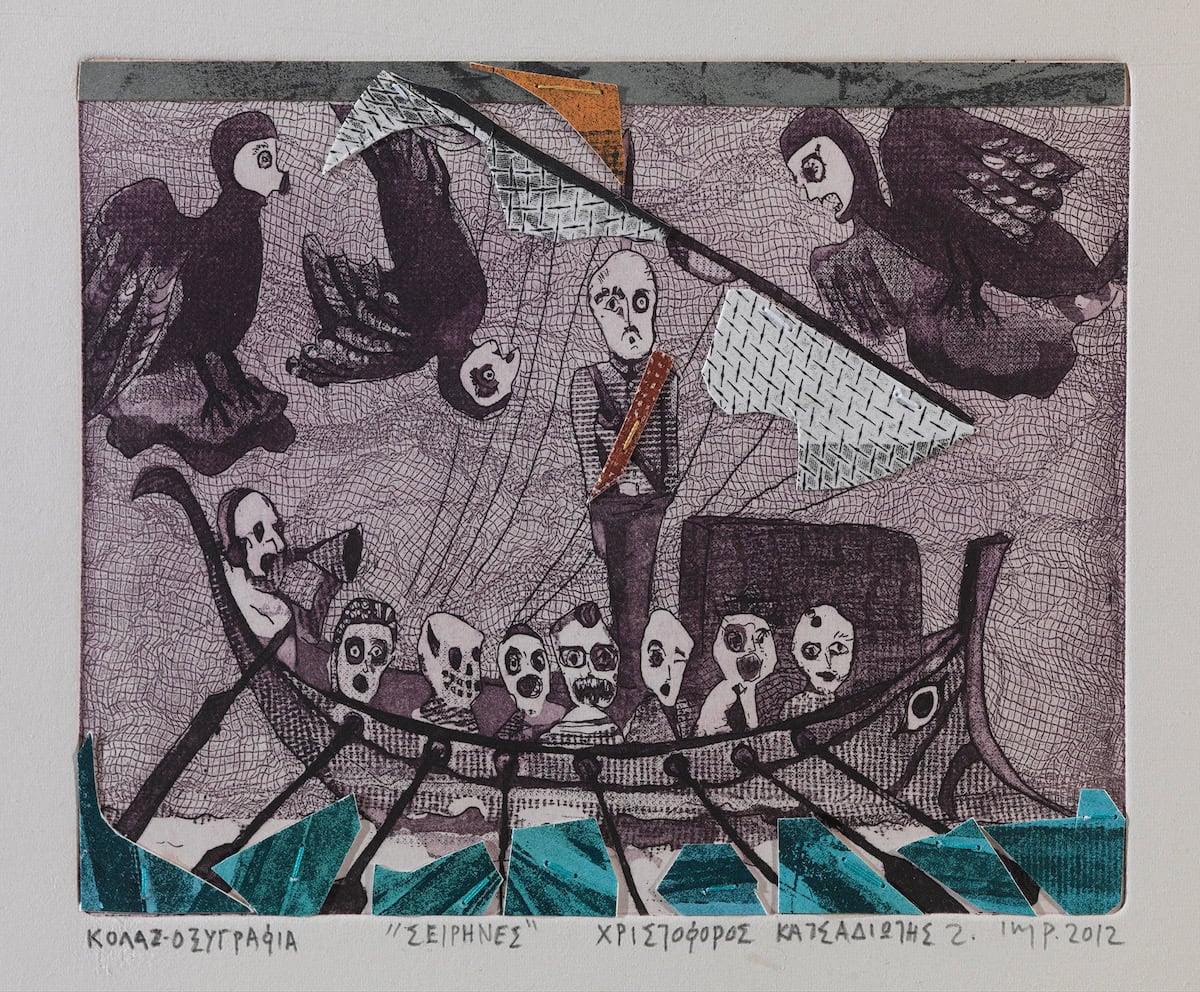

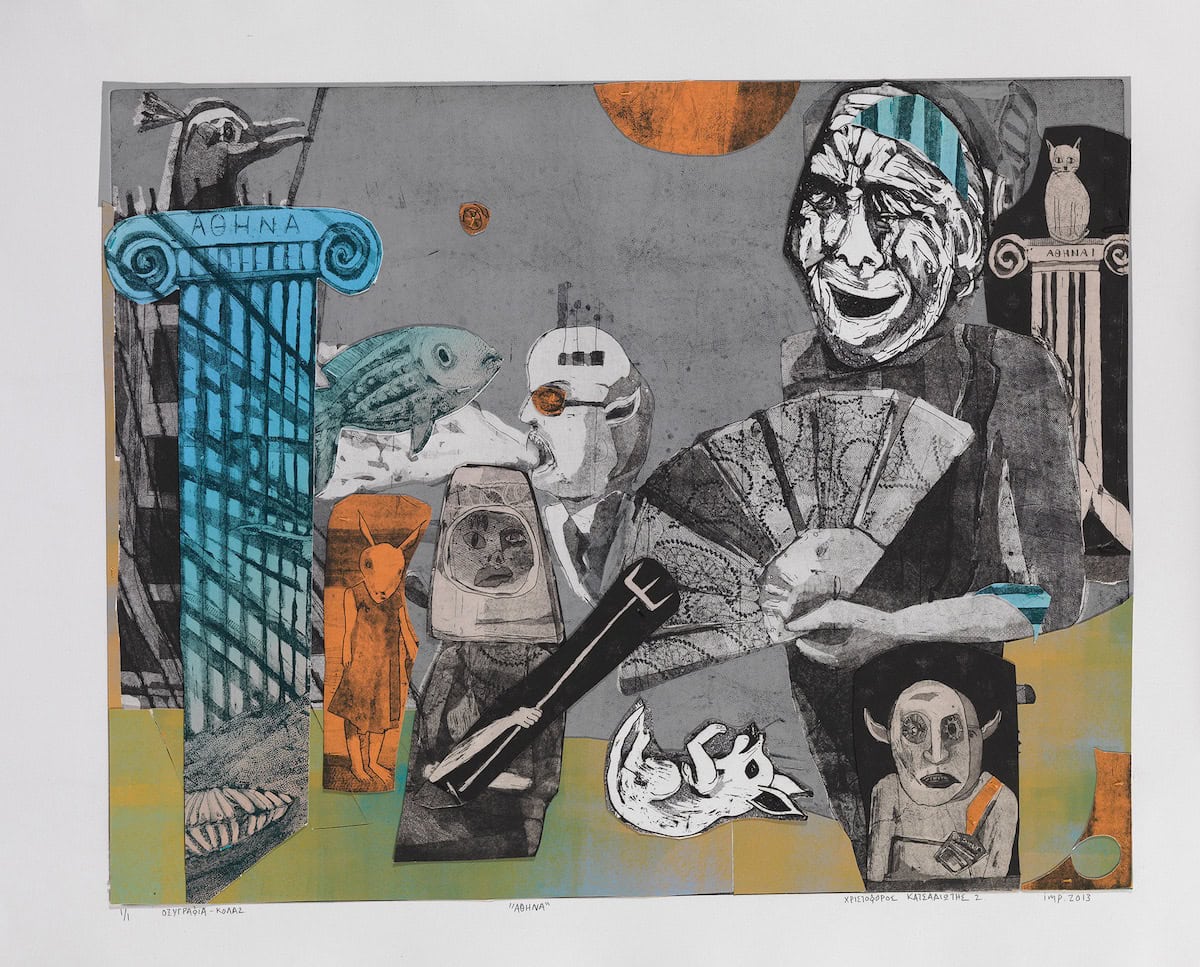

I’ve been checking out your artwork, and I’m really intrigued by a few pieces — specifically, five of them! I can definitely see there’s a lot of symbolism going on, but I’m a bit lost on the deeper meanings. I noticed some of them have ties to Greek mythology, which is super cool! Would you mind giving us a quick rundown of what each piece is about and any hidden meanings behind them? The pieces I’m curious about are Sirens, Athinorama, Trojan Horse, The Charm of the Unexpected, and Rue des Arts. Appreciate it!

I won’t give you a separate explanation for each artwork, simply because I don’t have the answers… as I mentioned earlier. The artist raises questions—they don’t provide answers. That’s not their role. It’s the viewer who speaks about what they see. And even though we’re all looking at the same thing, each of us gives it our own interpretation.

My characters embody the spirit of Odysseus and his companions, and I also find a close connection with Persephone. These people are torn between beauty and pain—how could they not be my ultimate heroes?

Without a doubt, all of them collectively honor, as they should, the god Dionysus.

Etymologically, there are two interpretations of the name “Odysseus,” and they complement each other. The first derives from the verb “odyssomai” meaning “to be angry” or “the one hated by the gods,” or in other words, the one who provokes displeasure. The second suggests it comes from “odynao”, meaning “to cause pain”—he is both the one who causes pain and the one who experiences it. After all, Odysseus constantly endures pain—spiritual and physical—causing pain to others, while others inflict pain on him.

Persephone is the queen of the underworld, associated with the dark and enigmatic, by common consensus, side of my work. A chthonic deity who received the souls of the dead into the earth and whose energy was so powerful it influenced the fertility of the soil over which she reigned.

Just as those mythological roles were politicized in their time through literary and poetic metaphors, my work is equally politicized in its themes.

The heroes in my engravings—and in my life—are the failures, the socially rejected, based on how society commonly defines and values these terms. These are people of decadence, of excess, of debauchery and the margins. People who are fearful, yet daring—often contradictory characters: wild, yet tender, with camouflaged sensitivities. Despite their typically rough, grotesque appearance, there is also a refined side to them. If the viewer wishes, they can sense their sweetness—hinted at in some detail, a movement, a garment, a glance, or a hesitation caught in a wrinkle of their gaze.

My heroes are primarily shadowy figures, belonging to an enclosed and trapped world.

Christophoros, I couldn’t resist the opportunity to share my thoughts on some of these remarkable artworks! I hope you don’t mind.

Your artwork, “Athinorama,” conjures up the Greek myth of Poseidon and Athena’s rivalry for the naming rights of an ancient city. In this dramatic tale, Poseidon offers a natural spring with his impressive trident, while Athena gifts a nurturing olive tree, winning her a huge fan base. Athena wins the contest, which is how Athens got its name. The real fun lies in Poseidon’s defeat, depicted with a bucket helmet perched on his head.

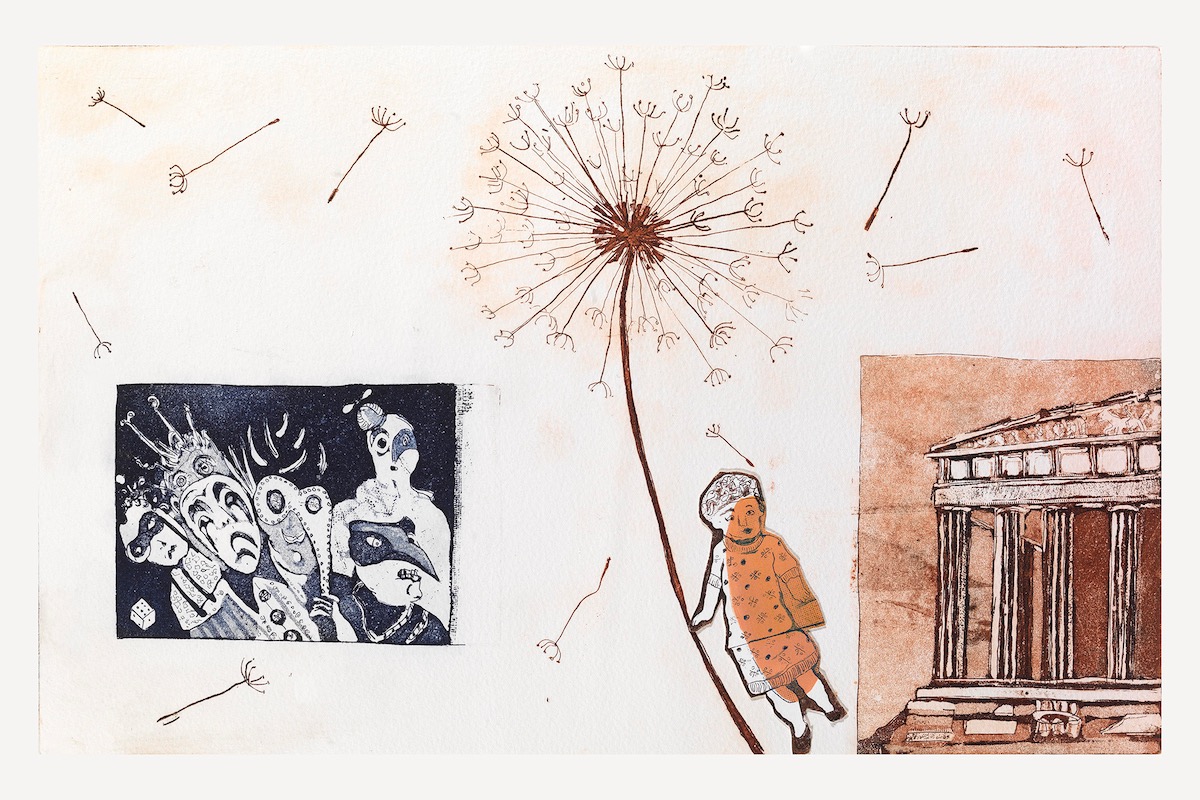

I inquired about “The Charm of the Unexpected” and “Rue des Arts,” but I see you chose to send me another artwork instead. I’ll interpret this choice as a sign from you or the universe that you believe this piece is better suited for the interview.

At first glance, this artwork enthralled me with its vivid depiction of conflict — arrows piercing toward a central sphere. On one side, the mighty Parthenon symbolizes strength, while the lively Carnevale on the other side evokes the joyful spirit of Dionysus. In between, a mysterious figure reminiscent of Athena stands poised, embodying the complex interplay of wisdom and power in a world caught between destruction and celebration.

Upon closer examination, my thoughts changed completely. Now the object resembled a “wishing flower,” much like a dandelion, evoking a sense of childhood nostalgia. When I eventually uncovered the title, “Carte Postale: From Greece with Love,” I was unfamiliar with the term “carte postale.” However, I soon learned that it translates to “postcard” in French. Thank you, Christophorus!

Let’s journey back to your childhood and youth. What kind of kid were you? Were you into sports, literature, or drawn to art from a young age?

I think everyone in my family had something artistic about them—very observant and good with their hands. But only a few of us managed to express it outwardly. One of my grandfathers, Angelos, loved tap dancing—Fred Astaire-style moves. The other grandfather, who shares my name, used to tinker with everything. My father had immense patience—he made architectural models and houses out of toothpicks. He would’ve been great at printmaking!

My mother had the sharpness and observational skills of an artist too—something that showed in her writing later in life. Reading her books now, I see traces of her in my own work.

And all of us in the family have a love for plants… Working with nature is therapeutic. We were close with many artists who visited our home. My mother encouraged me to apply to the School of Fine Arts when I was 17, but at the time, I didn’t grasp what that meant. I was clueless. She took me to museums in Greece and abroad from an early age—I don’t know how much of it stayed with me.

During school… it took me forever to get going. I struggled to adapt to the outside world for many years. I felt so lost. I don’t think I learned anything useful in school, nor did I get any sense of career guidance.

Instead of learning, I was being pressured and unlearning. I had learning difficulties and a long search for personal identity… Whole years went by that I barely remember—I don’t even see myself in them.

At 17, I volunteered for military service—two years. I figured I’d get it out of the way and free myself afterward. I always felt the urge to work with my hands. Among other things, I even volunteered as the “victim” for military dog training—wearing only a padded sleeve, no helmet, nothing else. This was in 1989. German shepherds were considered superior—those dogs had ranks; I was just a soldier. Pure madness. It was in Agiasos, a mountain village on Lesbos. At night, we could see the lights of Turkey…

I don’t know if my path would’ve been the same had I entered art school at the usual age. I probably wouldn’t have made the same work. Maybe I’d never have discovered printmaking…

For 15 years, I worked as a journalist—TV, radio, magazines—and during that time, I started creating wire sculptures. Then I began painting, self-taught.

In 1999, I had my first solo exhibition at the “Aigokeros” gallery of Christina Preka, showing wire sculptures and objects. In 2006, I had another solo show at “Peritechnon” gallery. That’s when Michalis Manousakis, professor at the Athens School of Fine Arts, invited me to his workshop as a guest—a gesture I deeply appreciate. That was my first real contact with the art world. At 37, I decided to take the entrance exams and got into the School of Fine Arts at Aristotle University in Thessaloniki. That marked a major turning point—I left Athens for the North.

Later, I spent nine months in Wroclaw, Poland, through the Erasmus program. I even had a solo show at the Paper Museum there. Those five years of study were the best years of my life. Maybe because I was older, I saw everything through a different lens. I worked hard—and had a great time.

When did you realize you wanted to pursue a career as an artist?

At 35, I was a guest at the Fine Arts School. A friend told me, “You’re just afraid to take the entrance exam.” I got stubborn. Started art prep classes… At 37, I passed and eventually graduated with honors.

Which artists do you admire most, and how have they influenced your creative journey?

All movements are important to me. I love studying art history—again and again. It’s endless. Sociopolitical events shape and give rise to artistic movements. But I was especially moved by the Weimar Republic era, the Russian avant-garde, Dada, Fluxus…

Is there a museum or art gallery that holds a special place in your heart?

Musée d’Orsay in Paris—to see Van Gogh, Gauguin, Courbet, and the permanent collections on Impressionism. Also the Pompidou. I’m addicted. Oh, and the Orangerie for Soutine…

Where are you currently based, and what inspired you to make that place your home?

I’ve been living in Paris for the past 12 years. I met a French woman on the deck of a ship and ended up in Paris. It just happened… Life circumstances. I believe in circumstances, not coincidences. Circumstances have purpose. Coincidences rely on luck…

Christophoros Katsadiotis: Interview Conclusion

Hey Christophoros, what an awesome interview! You’ve totally earned my admiration and respect, and I bet a lot of other readers feel the same way. It was such an eye-opener!!

Honestly, you give off serious vibes like a Greek Salvador Dali — total surrealist genius! I mean that as a huge compliment, especially considering my art knowledge is practically non-existent!

Sorry John, hahaha… Salvador Dali was a fascist. My grandfathers were Max Erst, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Ludwig Kirchner, etc….

Thanks for clearing that up, lol. It’s such an honor to have you as one of the interviews on Greek Gods Paradise. You’re the second visual artist I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing thus far, and I must say, both of you have completely blown me away. Seriously, you are both so brilliant!

My very first interview was titled “A Greek Odyssey: An Interview with Jeff Murray,” and it’s another must-read, especially for art lovers and fans of Greek mythology.

I’m really intrigued to know that you’re such a big fan of Odysseus! If you haven’t seen it yet, I highly recommend checking out “33 Movies based on The Odyssey (and Adaptations).” You might just discover an interesting film or TV series that piques your interest!

Also, your appreciation of Dionysus was totally unexpected. Good choice!

On a different note, if your artwork has stirred such strong reactions from the religious community in Greece, I can’t help but worry about the impact of my own creations — like my Athena and Hermes comics. I’ve joked about Scientology in my pieces on Tom Cruise and John Travolta, not to mention the many well-known figures I’ve poked fun at. They’re probably all out for my head, lol.

Christophoros, I also want to express my sincere appreciation for how you have referred to me as “my friend” during some of our conversations. It truly adds a warm and friendly vibe. Let’s definitely keep in touch! I wish you all the best with your artwork, and I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s worth an absolute fortune in the years to come.

I’m also excited to share that I’m starting my own art journey and will be showcasing my work on Greek Gods Paradise. I’ve already got my paints, canvases, and everything I need. Every masterpiece begins somewhere, right? Looking forward to keeping in touch!

Pin it … Share it